A Lesson in Faith

USD Magazine (Spring 2002)

By Susan Herold/Photos by Gary Payne ’86

Opening a private Catholic school in one of San Diego’s poorest neighborhoods is a huge challenge, but David Rivera ’96, prefers his challenges giant-sized. His students are labeled “at-risk,” his teachers have no experience, and money is a constant problem. Yet his belief in God gets him through.

A mouse is running loose in the tottering, two story Victorian David Rivera to house his volunteer teachers and it’s got him stumped. A visit from the Orkin man proved fruitless. Unsprung traps, picked clean of their food, taunt him. And now, the pricey electronic device that is supposed to emit a noise and scare away the furry thing, is discovered unplugged. The 10 teachers who live in the house (9 of whom are women) are understandably getting edgy. Rivera is starting wonder what kind of rodent he is up against.

It’s not surprising that a man who chose the most improbable of scenarios as his life’s work – opening a tuition-free, Catholic school in San Diego’s worst neighborhood, with a staff of greenhorn college graduates as teachers is playing David to a Goliath of a mouse. It’s a role he’s been comfortable in since the age of 26, when he decided that slaying giants in the form of social problems was his calling. Turning his back on a six figure income, a hilltop house and a player lifestyle, Rivera did what many consider unthinkable: he adopted a bare bones existence and an unshakable faith in God that compels him to serve others.

He has found himself serving a handful of 11-year-olds left behind by the education system, kids labeled “at-risk” because they are poor, can’t read or act out because that’s the only behavior they know. Rivera opened a one-room school in their neighborhood in September and promised a 12-hour school day, Saturday classes and breakfast, lunch and dinner. He filled the kids’ heads with dreams of a college degree if they committed to the demanding curriculum. He filled their parents’ hearts with hope.

Rivera used his considerable charm and determination to wheedle money and advice from community leaders frustrated with politicians’ empty promises to improve education. He lured graduates from the nation’s top universities to teach in exchange for room and board. He convinced his alma mater, USD, to help his rookie teachers become great teachers by covering most of the cost of their master’s degrees in education.

On this day, like most, Rivera is trying to do too much with too little. In between taking a delivery of donated copier paper and frantic calls about mutant mice, he is looking for more money to keep the small school afloat. The tired van that transports the kids to swim lessons is barely lurching along. About $18,000 in bills comes due each month and he has $6,000 in the bank. A promised big-money donation fell through because of the flailing stock market. Yet Rivera’s not worried. He believes in divine intervention, says God will provide. He has in the past — in October, with $19 in the bank, a donor came through to keep the school going.

“How big of a risk really is it?” says Rivera, now 34, of his decision to walk away from a successful career and try to improve education For San Diego’s poor kids.

“I could get a job doing anything tomorrow. There is no risk in it for me compared to the children and families here who have little hope or opportunity,” he says from outside his “house,” an 8-by.20.foor construction trailer behind the teachers’ home in Logan Heights. An extension cord snaking across rhe dirt backyard provides his electricity; he sleeps on a cot. His salary is $91 a week.

“These kids who come to school and these teachers who traveled a thousand miles to work here for nothing, they are the ones who are taking the risk,” he says. “Talk to them. They’re the story, not me.”

But you can’t tell the story of this improbable school without David Rivera. Those who signed on for his dream of giving low-income kids a first-rate education will tell you the sheer force of his will makes the school possible. “Would this school exist in San Diego without David Rivera? No,” says USD Provost Frank Lazarus. “To start a school like this takes a visionary with an absolute passion for getting it done. David has that.”

A little more than two years ago, Rivera walked into Lazarus’ office with nothing more than an idea – finding a way to help San Diego’s poor kids get a better life. He began by asking Lazarus the same question he had posed to other San Diego community leaders. “What is the biggest need these kids have?” The responses were identical: education.

So Rivera, who has no background in education, decided he would find the worst neighborhood in the city and come up with a better way to reach its kids.

He turned down job offers as an attorney that would have covered the $60,000 he owes for his Notre Dame law degree to move back into his parents’ San Diego house. He covered his bedroom walls with city maps, analyzed census data on income, crime and home occupancy, pored over tables on public school performance. The pushpins rose like a red welt out of Logan Heights, a hardscrabble neighborhood east of downtown, where the annual household income is $18,000 and the population is two-thirds Hispanic.

Rivera had a neighborhood. Now he needed a plan. On a flight to a friend’s wedding in Philadelphia, Rivera leafed through a Parade Magazine and found a story about Nativity Prep schools. Started 30 years ago by a group of New York Jesuits, the Nativity Prep philosophy contends that 12-hour class days, a low student-teacher ratio, college-prep work and a healthy respect for Catholic values will lead at-risk children to success. The concept works: 80 percent of the children graduating from the original Nativity Prep in New York have gone on to college. There are now 40 similar schools throughout the country.

When Rivera’s plane landed, he rushed to a phone booth, looked up the address and found Philadelphia’s school. After meeting the well-mannered kids, who talked about their plans to go to college despite their circumstances, he knew what he wanted to create.

Rivera parked himself in the principal’s office at the University of San Diego High School to learn as much as he could about running a school. He set up meetings with experts like USD’s School of Education Dean Paula Cordeiro and veteran Catholic school principal Brian Bennett. He picked their brains, asked for their help and created an education advisory board.

“There was nothing in San Diego similar to Nativity Prep, a school that deals specifically with very, very low-income students and develops a Catholic relationship,” Rivera says. “I told my advisers about it, and they said, ’Go out and do whatever you need to make it happen.’”

Rivera did. He got help writing a business plan and a needs assessment to get funding for the school, landing 5300,000 in grants – including 550,000 each from San Diego companies Sandicast and Hoehn Motors, and S120,000 from the Catholic Cassin Foundation—on little more than his passion. “I had no idea what a needs assessment was,” Rivera says. “I was embarrassed to tell Dean Cordeiro that when she said I needed one.”

He convinced one of his advisers, veteran Catholic school principal Bob Heveron, to come out of retirement and run the school. Rivera had to hire teachers, bur had no money for salaries. With USD’s help he discovered that AmeriCorps would send him volunteer teachers, college graduates interested in service work for two years. To make the deal sweeter, he convinced Lazarus and USD to pick up most of the tab for the teachers’ graduate degrees in education.

Rivera and his advisers decided the school should start out teaching fifth graders. Eleven-year-olds, they reasoned, had yet to hit puberty, and hopefully were not drawn in by the gangs and drugs and sex that filled their streets. They’d reach the kids through their parents, pitching the school during Mass in neighborhood parishes, posting fliers, going door-to-door. It was last summer, and Rivera wanted classes to begin in the fall.

“People said I should slow down, consider other areas of San Diego, wait,” says Rivera. “But the need was too great. I wanted kids in those seats.”

It was a great plan, a beautiful dream. And it had next to no chance of coming together.

Two thousand miles from San Diego, Tracey Pavey hung up the phone. The Notre Dame graduate just promised Rivera, who she had met via e-mail, that she would teach at his school in San Diego, a city she had never visited, for two years for $35 a week.

Pavey was thrilled. She always had teaching in the back of her mind, although she majored in business. The thought of giving it a try ata new school for low-income kids appealed to her altruism. Her mom was worried about her moving halfway across country; her dad thought she was nuts for pitching a Notre Dame business degree in favor of volunteer work.

But Pavey liked the idea of receiving a USD master’s degree without having to take out a loan. She liked what Rivera told her about living in a big house, a la MTV’s “Real World,” with other college grads who wanted to help poor kids. She liked the idea of putting her business background to use in a start-up education venture.

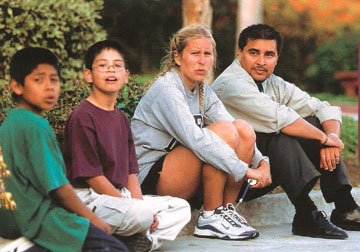

“I thought it would be cool to be in on building a school from scratch,” says Pavey, who hails from Rushville, Ind. With her dishwater blond hair hanging at her shoulders, her clean-scrubbed face and broad smile, the 22-year-old looks more like a big sister than a math teacher who answers to the name Ms. Pavey.

“I e-mailed and talked to David several times, and he convinced me to move out. I get out here, and there is nothing. No school. We don’t even have a house to live in. I thought, ’Are you kidding me?’”

When Pavey and the other teachers arrived last August, their house – which was the site of several recent drug busts – was still in escrow. The building Rivera hoped to lease for the school had been rented to another tenant. Nativity Prep was to open in six weeks, and it didn’t even have students.

“David told us that everyone in the county knew about Nativity Prep. My first day here, I passed out fliers about the school in the neighborhood, and people were saying ’What new school?’ ” Pavey says. “They hadn’t heard of us. It was frustrating.”

While waiting for escrow to close on the six-bedroom, two-bath house that had been turned into apartments, Rivera scrambled, moving the teachers from donated dormitories at USD to a Best Western hotel. When keys to the $205,000 house were turned over to Rivera, a woman and her five grandchildren were still living in the upstairs flat. The electricity didn’t work in two of the bedrooms. The kitchen and bathrooms were filthy. The transplanted teachers had to rip up carpet and knock down walls, doing much of the work by candlelight.

Teacher Margaret Liegel lived out of her suitcase in the living room with another teacher for nearly three months. Her room was the one occupied by the grandmother, who Rivera didn’t have the heart to evict until she found another place.

“We had to go out and get donations to get the house fixed, and we’re washing walls with cockroaches running out,” says Liege!, who graduated from Boston College. “I think I came out here thinking this is a really cool thing we’re doing, and then it hit you, oh my gosh, what am I doing here?”

A few weeks before classes were to begin, Rivera signed a lease on an empty building in Logan Heights for the school. Seven days before the doors opened, the teachers hosted an open house for interested families. They scattered the few textbooks they had throughout the room to make it more impressive.

“We were rearranging stuff to make it look like we had something,” says Pavey. “We didn’t even have bulletin boards. I thought the families would turn around and walk out.”

They didn’t. Nineteen children enrolled, and Rivera’s school had its first class. Driving through San Diego’s Logan Heights neighborhood, you would miss Nativity Prep Academy unless you knew exactly what to look for. The one-room school is in a squat, concrete structure tucked between warehouses and plywood homes behind chain-link fences. A hand-painted sign with the school’s logo – a white dove soaring over the three-story schoolhouse – is propped up against the curb. The only hint that children may be here is the lone basketball hoop in a corner of the parking lot, which doubles as the playground.

Inside, Liegel clears off some space from a table piled with papers to pore over her notes from her language class. Each day, she and the other teachers prepare incredibly detailed reports of their students’ progress and behavior. When parents arrive at 7 p.m. to pick up their kids, the teachers hand them the reports. They’ll pull a parent aside if they have a concern. It’s just one example of the intensive approach the school takes. “A lot of these kids were sullen when they first came here, they never smiled,” says Liegel, 23, whose glasses and ponytail enhance her rep as one of the “hard teachers among the kids.

“They pretended they were tough because in this neighborhood they had to. Here, though, they can be kids.” If a child is having a bad day or acts our, a teacher’s first instinct is to phone the parents and find out what is going on at home. In one case, a student’s big brother was getting out of prison and moving back into the house; in another, a student missed school because the family lost their apartment and was living at the Sr. Vincent de Paul shelter.

Nearly all the students have special needs – most tested at or barely above third-grade level in reading and math. Some have trouble speaking and understanding English. Every one of them comes from the neighborhood’s public schools, where they were promoted from grade to grade along with the rest of the kids.

To make sure the children get the attention they need, two teachers are always in the classroom; usually there are four or five. Reading, language and math are taught in blocks. Lesson plans are theme-based: a week may focus on insects, so students do math problems, write a research paper and do experiments revolving around bugs.

Religious studies, art history, physical education and social skills also are taught. The kids are awarded points for good behavior – raising their hand, saying please, not talking out of turn – and use the currency to buy computer time, pencils or notebooks.

“It’s almost a 180-degree change from what (schools) these kids came from,” says Principal Heveron, who began his teaching career in Los Angeles’ Watts neighborhood in the 1960s. “We don’t fault the public schools, because we know the pressure they are under with large class sizes. What we are doing is showing these parents and kids we are committed, that we are in this for the long haul.”

The commitment is evident in kids like Francisco. When he first came to class, he could barely speak English, could not read or write Spanish or English and could not distinguish letters. Half the time he fell asleep in class. The teachers weren’t even sure he attended school because his school records never materialized.

Francisco was tutored privately – an impossible luxury in public school. While the other kids took tests on geography, Francisco, who didn’t know the difference between a city and a state, received private lessons. Today, he speaks English, reads simple books and looks his teachers in the eye when he speaks.

“He has come so far,” says Pavey, who can’t help but worry about the kids when they leave for their homes each night. “I hope we teach them there is more than violence, drugs and gangs, and that they are capable of going on to college. But in the community they grow up in, college isn’t something parents push the kids into.”

Some educators are critical of programs like AmeriCorps or Teach for America, saying that sending inexperienced teachers to tough areas is a recipe for failure, because they are not prepared to deal with the issues of inner-city life.

Liegel counters by saying her classes at USD have filled in any gaps in her teaching methods, and that Heveron and her professors help with the day-to-day problems she faces. She and the other teachers say what they learn in USD classes at night is applicable the next day.

Most important, Liegel says she has learned more about herself from kids like Francisco than she thinks she could ever teach them. “There are times when the kids are driving you crazy and you think, why are they acting like this?” she says. “Then you remember that their father is gone or their brother is in prison. And you are amazed they can even get up and go to school on a regular basis.”

One aspect of the Nativity Prep model that especially appeals to Rivera and his supporters is that the school is an integral part of church and neighborhood. Rivera and the teachers live in Logan Heights, shop at its stores, worship in its churches. The Mission Valley YMCA provides free swimming lessons and summer camps, and county health workers give medical screenings at Nativity Prep.

“No school is just a school, not in the inner-city,” says Heveron, who watched as several Catholic elementary schools left the inner-city for the suburbs in recent years (Nativity Prep receives no financial assistance from the Catholic diocese but does get support from individual parishes). He came out of retirement to run Nativity Prep in part because of Rivera’s relentless enthusiasm, but primarily because he believes in its educational philosophy.

“I inherited 10 enthusiastic teacher volunteers and a warehouse with next to nothing in it,” he says. “Together, and with all the other help we’ve received, we’ve made this school happen. We did it by holding on to the vision David created.”

Rivera wasn’t always such a visionary. For much of his young life, he slid along on his incredible charm, his athletic ability and his good looks. The third of four boys growing up in the Skyline area, he tagged along with his parents, vibrant leaders in San Diego’s Hispanic community who knew political and church leaders on a first-name basis. His father co-founded several nonprofits and helped immigrants find jobs; his mother had a 35-year career as a social worker for the county.

Rivera stayed up late as his dad cooked carne asada for friends. He got used to the bishop dropping by the house after Mass. He loved the social whirl that surrounded his parents, but cared little for the issues. Rather, he dreamed of being a pro athlete and spent his free time playing basketball, baseball and football at Helix High School. Rivera was the kid who showed up early and stayed late for practice. Because of his small size, he often played hurt.

He bounced around between a half dozen community colleges on various athletic scholarships, playing football and baseball. But Rivera’s dream ended when his ankle shattered during a botched play. He left school with a 1.47 GPA and four metal screws in his leg.

“I quit school, came back to San Diego and got a real estate license,” he says. “I wanted to make a lot of money and I didn’t want to work too hard.”

He researched the market and discovered that the west Lemon Grove area of the city had few real estate agents. In his first year of selling, he made $1,200. By year three, his commissions totaled in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. By then he had the hot car, the great house, the big-screen TV the all-night parties. Bur one moment changed his life – when God mapped outr, with absolute clarity, his life’s mission.

“I’ve tried to describe that night before and I never can get it right,” says Rivera of Oct. 16, 1993, the date of what he calls his religious conversion. He falls silent for a few moments before he begins. ” It late at night and I was wide awake, looking out the window and the lights below Mount Helix, just reflecting. I had been all about athletics and wealth up until then and I just wasn’t satisfied. I was just really disgusted with my life.

“And then,” he says, “I was overcome with thoughts that I knew weren’t coming from myself.”

Those thoughts included a blueprint for his future: Graduate from USD, attend Notre Dame Law School, return to San Diego and help its poor children by starring a non-profit venture. That night, Rivera quit his realty job by leaving a message on his boss’s answering machine. That weekend, he sold most of his possessions, put his house up for rent and gave his big screen TV to his stunned brother.

By Monday morning, he was sitting in a USD counselor’s office, asking what it would take for him to get accepted. “USD is the Catholic university in San Diego, and there were certain relationships I needed to develop there,” says Rivera, who hadn’t attended Mass in 11 years but later was a leader in University Ministry.

“I was leaving a certain type or lifestyle and taking on a new one with God at its center. And USD is where I had to be to do it.”

Rivera took the slate of community college classes suggested by the counselor, got good grades and was accepted into USD. In 1996, he graduated with a 3.4 GPA in political science and philosophy. He then focused on getting into Notre Dame Law School – another step in the plan. Placed on the wait list, he campaigned for admission by writing a letter a week to the school’s dean. He even had a going away party for himself at his parents’ house, even though he had no guarantee he would get in.

“Part of me thought David was nuts,” says Mike McIntyre, USD’s director of University Ministry, who ministered to Rivera while he was a student. “The other pan of me thought if anyone could make it happen, Dave could. He doesn’t take no for an answer, and I mean that in the best sense of the term.”

Rivera showed up on the first day of law school orientation and planted himself in the dean’s office. When the dean’s secretary – who opened the dean’s mail – asked Rivera his name, she came over and gave him a hug. “She went and got the dean, who came out after a few minutes and said I was in,” says Rivera. “I had no doubt. It was pan of the plan.”

As always, Rivera has more to his plan. He intends to enroll a new crop of fifth graders this fall, and provide sixth grade instruction to the current group of students. Most of his volunteer teachers are committed to a second year, and 65 college seniors already applied for the new teaching positions.

But Rivera dreams big. He sees the Nativity Prep model eventually expanding from kindergarten through high school, teaching thousands of students and including a residential component. To help make that a reality, this month he will join Nativity Prep adviser Brian Bennett in a proposal before the San Diego Unified School Board to open a K-5 charter school in Logan Heights that, like Nativity Prep, includes a 12.hour school day and volunteer teachers.

With charter school status comes a guaranteed stream of income to run the school, eliminating one of the major hurdles that Nativity Prep now faces. In exchange for the state money, however, the new school could not be designated Catholic, to preserve separation of church and state. Rivera doesn’t see that as an issue. Because the school day is longer than that required by the State, he says religion would be offered as an elective, afterschool activity. “It’s big,” he says of his plan. “We’re talking about thousands of kids in a college prep program in the lowest income areas of San Diego. It will go K-12. Absolutely.”

Part of his plan relies on USD, which Rivera would like to help supply and train more teachers. Aware of the financial burden an expanded program could mean (USD currently covers about $180,000 in tuition costs for Nativity Prep teachers), and wanting to maintain autonomy between USD and Nativity Prep. Lazarus and Cordeiro are looking at ways to possibly expand USD’s assistance if the school grows.

One option may be to partner with a None Dame program that gives students interested in serving low-income areas a crash course in education before they are sent out to teach. Many of USD’s undergraduates join VISTA or the Peace Corps, and Lazarus sees this as a way for them to serve their local community (several USD seniors have applied to teach at Nativity Prep this fall). Alternative means of delivering the master’s curriculum to the teachers also may be considered.

Lazarus is cautious about the loss of independence that comes from a charter designation, as well as the Catholic identity issue. Yet he says the Nativity Prep model is so vital to inner-city kids that it must carry on. “Will USD continue to support David whenever it can, in organizational as well as personal resources? Yes,” says Lazarus, who first became familiar with Nativity Prep through a school in his former hometown of Milwaukee. “There comes a time and place where people have to decide where they stand on education, and you have to do what it takes to make it happen. This is that time.”

If the charter designation isn’t granted, Rivera says with all earnestness that he isn’t worried. He says the Nativity Prep concept will carry on, because it works and because there are enough talented people supporting it. As he has in the past, he says God will see to it that the children will be taught.

In an uncharacteristic moment of uncertainty, Rivera wonders aloud if he might not be the best person to lead the school. He admits he gets easily distracted by the little things—mousetraps and copier paper. He worries that he doesn’t know enough about education, that his expertise lies more in raising money, raising hope. His humbleness refuses to let him take credit for what he has created. “’I think if I went away someone would come in and pick up the slack and do a better job,” he says.

“’This isn’t thriving because of me, it’s thriving despite me. The spirit is leading this and it has a life of its own. I’m just going with the flow of what the spirit wants me to do.”