Leap of Faith

San Diego Union-Tribune (January 20, 2002)

By Chris Moran

San Diego—Opportunity knocked on doors in Logan Heights and Stockton last summer, borne by a 22-year-old Midwesterner three months removed from life as a college student.

The white solicitor with the economics degree definitely wasn’t from the largely Latino neighborhood. But Lisa Martin made an alluring pitch, and in Spanish.

She asked people to send their children to a school with fewer than 20 students. Nativity Prep Academy would have at least two teachers in the classroom, and sometimes as-many as SLX, she promised. School would last 12 hours a day during the week and four hours on Saturday. The school would take care of breakfast, lunch and dinner. The curriculum would emphasize college preparation and Catholic values.

And Martin mentioned something that translates well in any language—this would all be free, gratis.

Martin was there because she had responded to a sales pitch herself to be a teacher at the school.

It came from David Rivera, an upstart University of San Diego graduate whose vision. was an ideal school for underprivileged children led him to trade in a four-bedroom hilltop house and the streaky money of real estate for a trailer without plumbing and the austerity of a pioneer.

Rivera is the 34-year-old son of Chicano activists from San Diego. His parents’ generation participated in movements for fair housing, equal employment opportunity and an end to discrimination. Rivera has gone the more solitary entrepreneurial route in the most high profile civil rights cause of recent years – the education of the urban poor and minorities.

He needed college-educated people to teach on Market Street, east of downtown San Diego, for $35 a week. In return for a two-year commitment, he pledged to give them a free place to live and cover their tuition and expenses for a teaching credential or master’s degree program.

He got 49 applicants. Ten showed up for this uncertain venture, but there was no school, no teacher’s home and Rivera had not yet lined up USD to train the teachers.

When asked how she knew everything would work out. teacher Caroline Sekula said, “I didn’t really. I just took a plunge. All of us, I think, just took a tremendous leap of faith in coming out here.”

Of course no one could teach until they had students. To find them, Rivera dispatched teachers to canvass the neighborhood, speak at churches and meet community leaders.

They braced for an open-house night to await the results of their door-to-door and pew-to-pew recruiting. They were nervous. Would anyone show?

The panic melted away as families showed up.

Margarita Vera, one of Martin’s recruits, was sold when she entered the warehouse on Market Street that would be the school’s home.

“They already knew the names of my child and myself,” Vera said.

Vera had been concerned about the social environment at her son’s public school, the fights, the lack of civility. Her son was introverted, she said. She could see academic ramifications for Jose, who had to compete with 30 other kids for a teacher’s attention.

But Vera didn’t feel she had a choice. She didn’t work, and her family couldn’t afford Catholic school on the salary her husband received painting trucks. Then she got the house call from Martin.

Rosa Herrera had been waiting for two years to get her son bused out of Logan Heights when she heard about Nativity Prep.

It wasn’t Logan Elementary School that concerned her. It was the after-school latch-key hours. She lives on a block where boys loiter, drink, smoke and sometimes do worse. She knows because her older son was one of those boys until he went to jail. She thought a 12-hour day would be just the thing to keep Adrian, 10, out of trouble.

Still, the choice came with risks. None of Nativity Prep’s teaching corps had taught before, and none had even majored in education.

However well-intentioned, programs that thrust rookies into schools in poor neighborhoods have been criticized because students in these schools need the very best instruction if education is to prove an economic equalizer. Instead. poor children are most likely to attend schools staffed by the least experienced teachers.

Kati Haycock, director of the Education Trust, a reform group that advocates for better schooling for low-income for black and Latino students, said not just any college grad can do what a teacher does. But if volunteer teachers are cream-of-the-crop college grads, she said, they may do as well or even better than first-year teachers with traditional training.

Brian Bennett, a veteran Catholic school principal and an advisor to Nativity Prep, said the low student-teacher ratio at the new school and the training from USD could offset inexperience.

In the end, though, he said parents were being asked to experiment with their children’s education. “These parents look a huge leap of faith,” Bennett said.

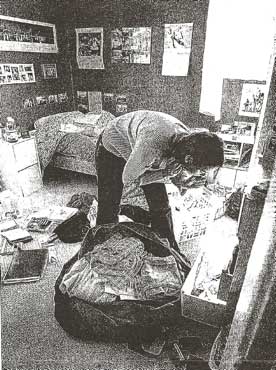

On the morning of August 20, escrow closed on a $205,000 house at South 31st Street and Martin Avenue. A house that only hours earlier had been the scene of a drug bust, was the new home of the teachers for Nativity Prep Academy.

Rivera, the founder who had raised more than $300,000 to launch the school, moved into an 8 by 20-foot trailer in back of the house. It’s his office and his bedroom, separated by a shower curtain. He leased property for the new school at 3275 Market Street, and he sealed the teacher-training deal with USD. Amid the challenges of serving 17 students this year, Rivera looks ahead to serving thousands. He sees the current crop of fifth-graders as the leading edge of expansion until they graduate as the class of 2009.

Furthering his commitment, Rivera will play a role in Bennett’s plan to open a 232-student charter school in Logan Heights in September. Bennett will seek San Diego city schools’ approval early next month. It would be Nativity Prep without the religion.

This is a calling. You don’t live in a trailer unless you feel you have a calling or a passion for a cause,” Rivera said, “and that calling is definitely religiously driven. My faith is why I’m here. My faith is why I work so many hours. Seven days a week, with no days off.”

The calling began October 16, 1993, a weekend night like many for Rivera, a 20-something college dropout who was making heady money in San Diego’s real estate market.

Friday night partying had ended early Saturday, and Rivera was alone in his big house. Maybe his activist pedigree compelled some altruism. Maybe the solitude triggered an existential reckoning. There was a void, and what rushed in to fill it was what Rivera calls a religious conversion. It came with instructions: Get a degree from USD, go to Notre Dame Law School, and lead a nonprofit organization to help at-risk children.

At 2 a.m. he called his boss and left a message that he was never coming back to work. Then he beefed up his transcript and grade point average at several community colleges, got accepted at USD and earned his degree. In 1996, he applied to Notre Dame Law School.

When he was put on the waiting list, he campaigned for admission with weekly phone calls inquiring about his status and a series of biographical chapters to supplement the information in his application. Finally, he just packed up, left San Diego and crashed orientation.

Then-Dean, David Link, had been examining Rivera’s epistles. When there was a no-show or two among the newly arrived law students, Link went to his waiting-list files and pulled Rivera’s dossier. In such cases, he said, it was his custom to call admissions and ask, “Do you think this person is still available?” The admissions counselor’s reply: “We’re sure he’s available, because he’s sitting outside your office.”

Law degree in hand, Rivera became a squatter in the principal’s office at University of San Diego High School. Rivera got a desk where he could research how to start a school and tap into Principal Dick Kelly’s contacts.

One was Bennett, a fellow law school graduate, and so began the partnership of two educators trapped in lawyers’ bodies.

Bennett saw Rivera’s proposal as a start-up with spirituality, a nonprofit in the service of literacy. Together they researched where they could do the most good, and the numbers pointed to an area in Logan Heights around Market Street that is 89 percent poor and 68 percent Latino. Average annual income for the families of Nativity Prep is $18,000.

To make the case for the need for Nativity Prep, they documented what they consider the educational neglect of a neighborhood. For example, they concluded that the abysmal test scores at a dozen public schools in the area meant parents have poor choices provided by the government.

Said Nativity Prep Principal Bob Heveron, who has 20 plus years experience in local Catholic schools, “That does bother me as an educator who’s worked most of his life in center cities.”

Nativity Prep Academy borrows from a model started by Jesuits 30 years ago in New York City. Nativity schools specialize in students who are behind academically and from poor families. Rivera said Nativity targeted fifth-graders because he perceives it as the point at which students start selecting “good” or “bad” peer groups. The original Nativity schools took a four R’s approach reading, ’riting, ’rithmetic and religion – in sending 82 percent of its students to college.

The rich have always had their choice of schools. They buy homes new the best public schools or pay tuition at the best private ones.

Nativity’s business plan says inadequate schooling is both the cause and effect of poverty. Its goal is to break the cycle of poverty through academics and character building.

“How do people overcome adversity?” Rivera asked. “Through education and faith.”

Rivera still receives an occasional jolt that raises anew the question of survival. Last month he carried his $91 weekly paycheck to the bank, and the teller told him the school’s account had insufficient funds. He said the $40,000 he raised later in the month should carry me school through the end of this month. After that is a question.

The stock market plunge exacerbated by September 11th caused a major donor to renege on a six-figure pledge. He said Nativity will need to come up with $120,000 to finish the school year.

Five months into it, the teachers now talk about the comfort of routine, one that involves 60 hours a week in classes as teacher or student or even as they cook preparing dinner for the students. Some split their volunteer teaching time between Nativity and other schools in the area – Logan Elementary, St. Jude’s Academy and a science education group called Aquatic Adventures. They knew it would be a lot of work, but they came from Notre Dame, Boston College and Colgate, schools that emphasize service.

After their workday, the teachers carpool to classes at USD, where they’d be paying thousands of dollars a semester for books and tuition were it not for their affiliation with Nativity. They say they apply their lessons learned in lectures the very next day.

Except for the length of the day and the religion, the academic schedule at Nativity Prep looks similar to that of other schools. After breakfast and a quick prayer meeting, there’s a two-hour language arts block. Then there’s two hours of math and after lunch. there’s a half hour of religion, and depending on the day, science, social studies, Spanish, theater or physical education.

Nativity’s leaders based the curriculum on state standards and private and charter-school successes. They chose books from state-approved publishers. Since about 60 percent of the students live In Spanish-speaking homes, the reading program is geared toward language acquisition.

What the kids and parents seem to like best about Nativity is its size and personal attention. Andres Navarette, 10, who went to school in National City last year, said at his new school, “the teachers are younger, and we get to do stuff like plays.” Every student was involved in the holiday pageant put on last month for parents.

Teachers are able to have one-on-one discussions after instances of mischief. They also have a yellow tally sheet for each student, on which they quantify conduct. With the accumulation of points come rewards. Brandishing the sheet with a threat to subtract from the total generally gets students to behave.

Nativity has started with the support of experienced educators. USD High Principal Kelly’ is on the board of directors. Its advisory board includes Frank Lazarus, vice president and provost of USD; Paula Cordeiro, dean of USD’s School of Education; and Jose Cruz, associate director of the San Diego Literacy Council.

Bennett said Nativity will succeed if parents stay happy and the school can keep committed teachers in one of San Diego’s poorest neighborhoods. “We just want to prove that it works,” Bennett said.

There’s not much evidence of academic success. Heveron said the students have shown consistent growth on the tests supplied with the reading program, but since they started nearly two years behind their grade level, on average, there’s a big deficit to close, “We’re dealing with young minds and this doesn’t happen overnight,” Heveron said. “We see steps, not leaps.”